The hidden tax of modern finance: reconciling siloed sources of truth

Reconciliation is the cost of fragmented systems, and it scales with every handoff, counterparty, and exception.

Traditional finance is decentralized in the worst possible way: everyone has their own ledger, their own reconciliation process, and bridges everywhere.

Reconciliation is a parallel production line whose only job is to correct the output of fragmented systems that all show only a partial view of reality: front office, risk, ops, finance… Reconciliation scales with volume, complexity, and counterparties: the more that is going on, the more complex and expensive these systems are.

Why reconciliation is so costly in traditional finance

Operational headcount

Reconciliation is extraordinarily labor-intensive. Post-trade operations are one of the largest fixed-cost centers in financial services companies, with global post-trade processing costs estimated at $20-40 billion per year in 2022 by EY.

Much of that spend goes toward exception handling: investigating breaks, chasing counterparties, or manually matching siloed records. BankBuddy estimates that the average cost of a single exception is $18 per incident, with transaction failure rates of 2% to 4%: this adds up very fast.

The contrast with newer infrastructure is very stark. For example, the onchain business OpenFX reported that a fast onchain settlement system allowed to allocate four full-time engineers to reconciliation operations instead of over 700 operational staff at legacy FX competitors, dramatically reducing costs.

Tools and integrations

No single tool covers the full data lifecycle and integrates with all data sources. In this context, institutions must stack vendors: ETL pipelines, middleware, data warehouses, reconciliation engines, controls and monitoring layers…

Each of these vendors comes with licensing fees and internal teams to manage it. Every counterparty also requires a new custom integration. Multiply that by asset classes, geographies, and internal systems, and the invoice blows up.

Moreover, the risk of overlap keeps growing, creating redundant tooling and fragmented data with nobody to keep track of the systems and of the rising total costs. Duplicate controls follow: each system runs its own validation, its own exceptions, its own audit trail, creating discrepancies and capital inefficiency.

Inefficiency and slowness

When data lives in silos, every process that depends on consolidated truth slows down.

Settlement windows stretch because counterparties need reconciliation before confirming positions. Month-end closes drag because finance teams are busy chasing breaks. Reporting lags: the « single source of truth » is actually a patchwork of data sources brought together clumsily.

Legacy FX corridors still take 2 to 7 days to settle, when newer infrastructure can clear the same transactions in under an hour. That settlement delays locks up capital, delays decisions, and compounds risk.

Control and detection

Reconciliation is not a control function: it’s a detection step that catches errors after the fact. When an issue surfaces days later, the window for correction has closed, positions have moved, and fixing the mistake can come at a staggering price: settlement failures alone have cost the industry an estimated $1 trillion over the past decade, according to Citigroup.

Worse, some errors never surface at all. They hide in timing mismatches or reference data drift, until they suddenly come to the surface at the worst moment: an audit, a client complaint, a regulatory inquiry… Outside of the classic risk of failed reconciliation, we cannot overlook the cost of a reconciliation that succeeds just often enough to create false confidence.

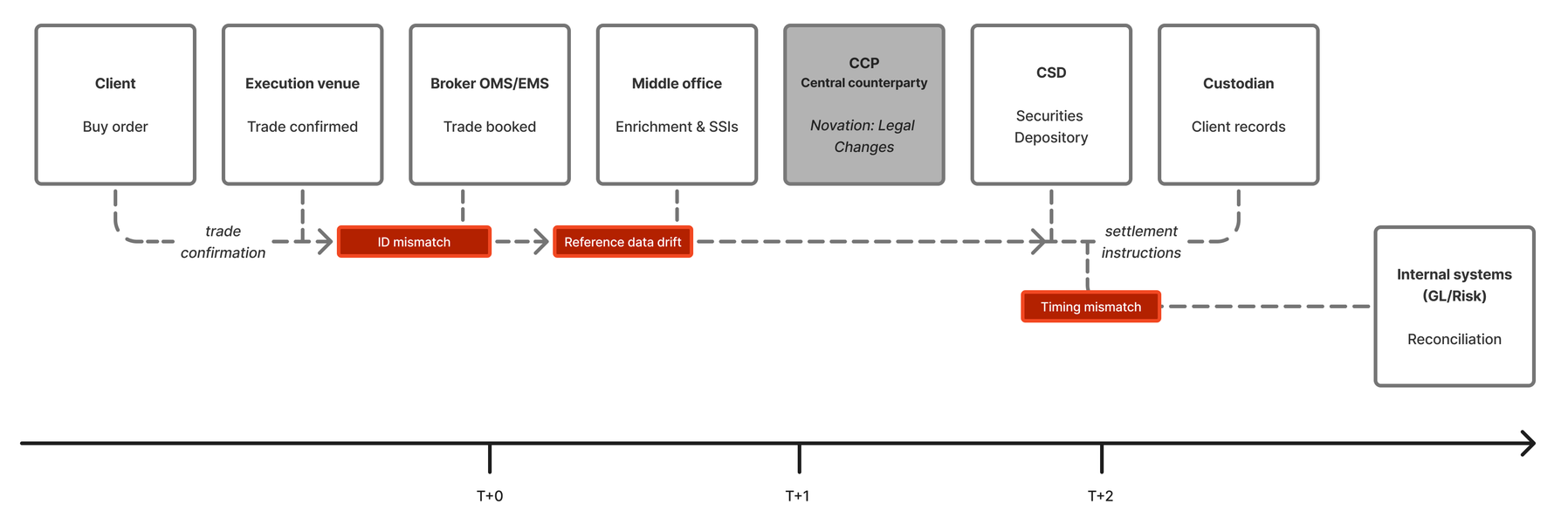

Practical case: a client buy order

A single equity trade touches half a dozen systems before it settles. Each system holds its own version of the truth, and each handoff is an opportunity for data to drift.

The journey of one trade

A client places a buy order. Within seconds, the execution venue confirms the trade: instrument, quantity, price, counterparty. That confirmation is the first authoritative record.

The broker's order management system (OMS) books the trade internally, assigning its own identifiers. Middle office enriches the record: client references, allocation instructions, standing settlement instructions (SSIs). The data is now richer, but also more fragile. Any mismatch between the OMS and the SSI database creates a break downstream.

If the trade clears through a central counterparty (CCP), novation changes the legal relationship: the CCP becomes the buyer to every seller and the seller to every buyer. The CCP's records reflect a different structure than the broker's books.

At settlement, the central securities depository (CSD) updates positions and issues settlement instructions. The client's custodian updates its own records and generates statements. Meanwhile, the broker's general ledger and risk systems reconcile against all of the above, often with a lag, and often using yet another set of identifiers.

By the time the trade settles, the same economic event exists in at least six systems, each with its own schema, its own timing, and its own version of the truth.

Where breaks happen

The points of failure are predictable. They recur across asset classes and geographies:

- Identifier mismatch. The OMS uses an internal trade ID. The CCP uses a UTI. The custodian uses an allocation ID. Mapping between them is manual or fragile.

- Timing mismatch. Systems run on different cutoffs. A trade booked at 4:59pm may land in today's batch or tomorrow's, depending on where you look.

- Reference data drift. SSIs change. Static data versions diverge. A counterparty updates their settlement instructions, but the update propagates unevenly.

- Corporate actions and partials. Stock splits, partial settlements, and failed legs amplify exceptions. Each one multiplies the reconciliation workload.

Reconciliation exists because there is no shared state, only messages. Each system reconstructs its view of reality from inbound data, and each reconstruction is a chance for error. The problem is not that systems fail. The problem is that success depends on every system agreeing, every time, with no single source of truth to arbitrate.

From messages to shared state: onchain settlement

Traditional finance coordinates through messages: each party maintains its own ledger and reconciles against incoming data.

Discrepancies are the natural result of parallel systems reconstructing reality from fragments.

Leveraging a shared ledger

A shared ledger changes the operating model. Instead of sending messages and hoping they match, counterparties write to a common state: the trade exists in one place, with one schema, at one time. This removes the need to reconstruct data entirely, eliminating the potential for most reconciliation errors.

This gives institutions three things they cannot get from message-based coordination:

- A single source of truth

- Append-only history recording every change for easy audit

- Deterministic settlement: only if conditions are met does settlement happens. There is no ambiguity about whether a transaction is final.

A shared ledger removes a large class of reconciliation work by making parties write to the same source of truth, rather than exchange messages about it.

The privacy constraint

For institutions, this only works if privacy, permissions, and compliance are preserved. Sensitive transaction data cannot sit on a public chain: regulators and clients expect confidentiality, competitors should not see each others’ flows.

Modern cryptography makes this possible, for example through zero-knowledge proofs, the cryptographic approach we’ve chosen at Hyli. This approach keeps sensitive data off-chain and posts cryptographic proofs without details onchain.

The technology exists to get the benefits of shared infrastructure without sacrificing the privacy that institutions require.